And a first look at differential equations

At some point in the past, I believe you learned a little about radioactive decay and half-life.

Here are some things that you may remember:

1. The size of a radioactive sample is can be expressed as a function of time:

N(t)=Noe-kt

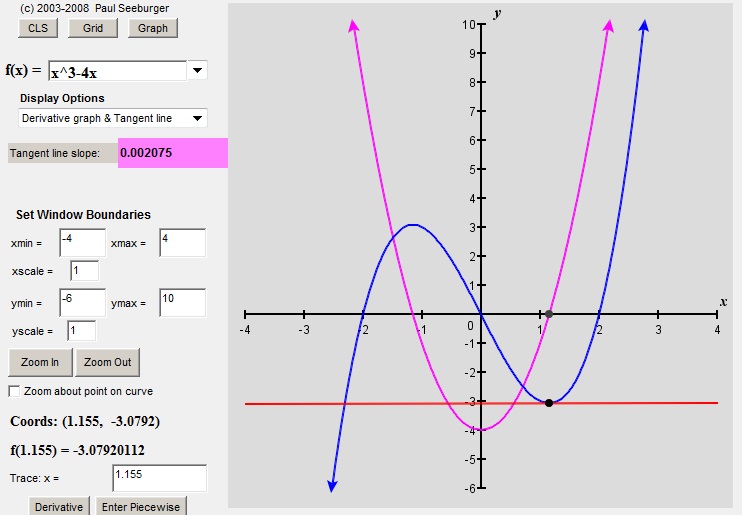

2. The graph of this function looks like this:

Note that at time = 0, the value is No and then the value decays asymptotically toward zero.

3. Graphs like this show up in many other contexts. For example, this looks a lot like the graph of current vs. time for a charging capacitor. It also looks like the graph of acceleration vs. time for an object in free-fall with air resistance. And there are a number of graphs associated with motors and generators that also have this shape.

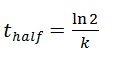

4. When a quantity decays exponentially, in equal time intervals it will decrease by the same factor. Most notably, the time it takes to decrease by 50% is called the “half-life”. There is a useful formula relating the half-life to the decay constant:

Do NOT just memorize this – derive it for yourself. If you need help getting started, you can begin by letting N(t)= ½ No.

*** To see that this claim about half-life is true, you can play with Part 1 of the desmos activity here: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/ooewvdzrmq

However, all of this assumes that we already know that the function is N(t)=Noe-kt . But how do we know that? When you see exponential decay, you should suspect that somewhere behind the scenes lurks something called a differential equation. And that brings us (finally) to the topic of this post.

WHAT IS A DIFFERENTIAL EQUATION?

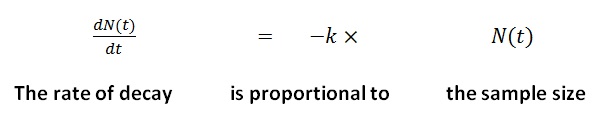

“The rate at which a given radioactive sample decays is proportional to the size of the sample.”

I hope that sentence makes sense to you, intuitively. It is saying that when there are more nuclei available to decay, the decay rate is faster. As the sample shrinks in size, there are fewer available nuclei and so the rate slows down.

*** This claim can be investigated further in Part 2 of that same Desmos activity: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/ooewvdzrmq Really, go do this now! I’ll wait here…

OK, so the rate is proportional to the current value.

But that sentence can be re-written using mathematical symbols:

The resulting equation relates a function, N(t), to one or more of its derivatives. In this case, the highest order derivative is the first derivative so this is called a “first order differential equation”. We are going to encounter a number of these in AP Physics and also a handful of second order differential equations as well. You will learn how to solve some of these in math class this year. If you continue in math and science, you may spend a number of semesters learning more about this topic. For now, I am going to show you a method that will be sufficient for our specific needs.

WHAT IS A SOLUTION?

When you solve an algebraic equation, you find a number that you can use in place of the variable, thus obtaining a true statement. For example, x= 3 is a solution to the equation 2x + 4 = 10 because when you replace x with 3 in that equation, you get a true result. And even if you didn’t learn the step-by-step method of solving that equation, you could still verify that x=3 works. It wouldn’t matter if the solution came to you in a dream! Once you verified it, you’d know you were right.

Now we have a different kind of equation:

We are not looking for a number. We are looking for a function, one that will make a true statement when we use it to replace N(t) in that differential equation. Here is how we are going to do this:

(Don’t worry if this doesn’t “click” at first. We will walk through this several times.)

1. Based on our intuition, draw a graph of what the function N(t) will look like.

2. Use our extensive knowledge of pre-calculus to guess a general form of a function that has that a graph shaped like the one we just drew.

3. Take the derivative of our guess (and second derivative if needed).

4. Substitute back into the equation we are trying to solve to see if we get a true statement.

If we have guessed correctly (as we often will), we will actually pick up some bonus information. Follow along with me and see what I mean. We’ll start from the beginning.

We are seeking a function N(t) that will satisfy this differential equation:

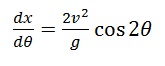

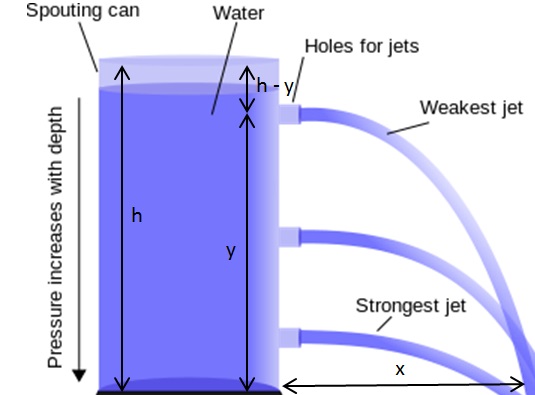

1. Our intuition about radioactive decay suggests that when we find the solution, its graph, as we already noted, will look like this:

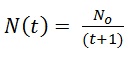

2. There are a number of functions that have that shape. For example, it could be that:

It’s not a terrible guess. It has the right value at t=0 and it approaches zero asymptotically. I don’t remember seeing that function used to model decay before and it would be all wrong for t approaching -1, but let’s try it anyway.

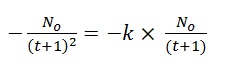

3. Taking the derivative, we get…

4. Now, substituting the function and its derivative back into the original differential equation, we get:

Hmm…can this be true? For a given value of k, it is true at some particular time. But we want a solution that is ALWAYS true. There is nothing we can do to fix this one. It turns out that our initial guess, though not terrible, was wrong. OK, new guess. Let’s try an exponential function. Our memories from pre-calc give us high hopes for this one:

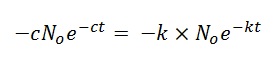

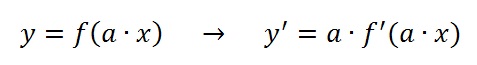

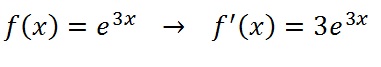

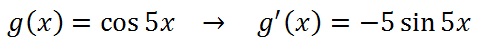

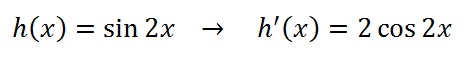

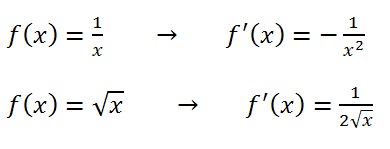

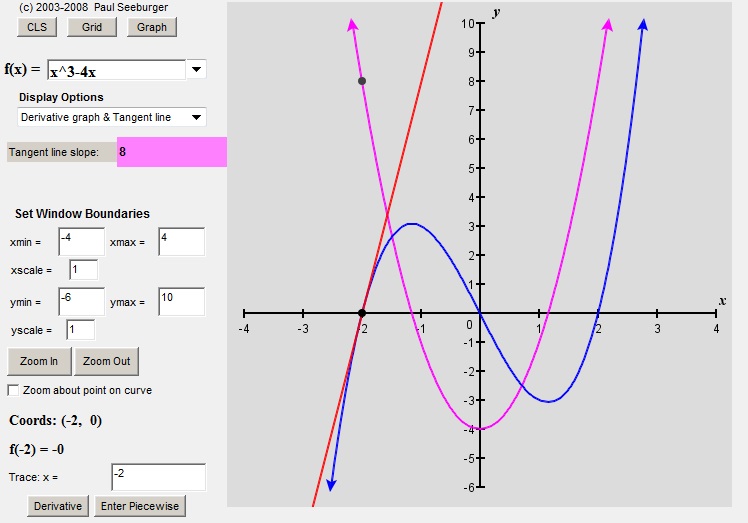

In this case, we would have the derivative:

(because the derivative of “e to the something” is “e to the something” and then there is that chain rule multiplier.)

But what happens when we substitute these expressions back into the original differential equation?

Can this be true? Why yes, but only if c = k. In other words, we have just learned that we had correctly guessed the general form of the solution but it can’t be just any old exponentially decaying function. The decay constant in the function has to match the constant of proportionality in the original differential equation. So with that adjustment, we have our solution:

This kind of thing happens a lot when we use this technique. At the end of the process, when you ask, “can this equation be true?” you get as the answer: “yes, but only if…” followed by some new information that tells you the required value of some constant.

Closing remarks

Please do not worry if you have found this post to be challenging. In the next practice set, I will give you a couple of additional examples and walk you through this process step-by-step. And we will also do a couple together in class. But review this a few times and you may realize that it is just another way to make use of derivatives and we still have not used any rules beyond the ones I showed you in the earlier posts. But that does not mean that this was easy!